Parenting and Children

Parenting and Children

Separating is difficult. Separating when you have kids can be a complete emotional rollercoaster.

While things are not always simple, one thing is clear – it’s important that you put your needs and your children’s needs first. This may mean you need the support of your family and friends, or you may want to talk with a counsellor or psychologist.

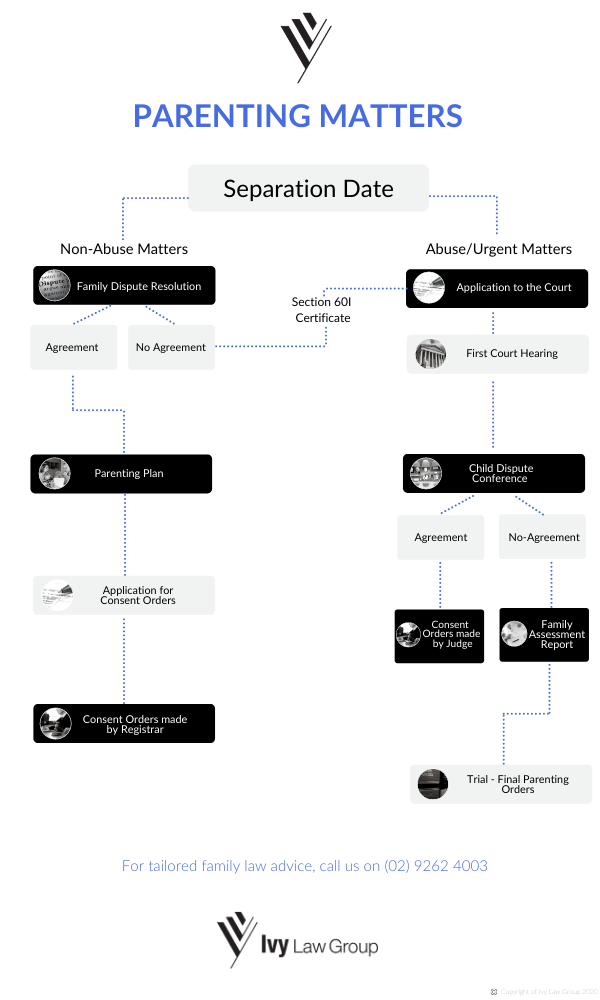

When you separate, you may need to attend mediation (known as Family Dispute Resolution) to negotiate an agreement, or commence proceedings in the Court if an agreement cannot be reached. You will also need to get legal advice to help you navigate your way through the family law system.

If you’re ready to get family law advice, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Children and Family Law

When making arrangements for your children, you need to consider family law legislation and the way that the Court approaches parenting disputes. This is true regardless of whether your parenting matter goes to Court or not.

The Court always approaches parenting matters by:

- applying the presumption that the “best interests of a child” is the most important consideration

- recognising that each parent has parental responsibility towards their children (which is generally shared equally, unless there are reasonable grounds to believe a parent of the child has engaged in family violence or abused the child.)

What does the “best interests of the child” mean?

The best interests of the child are, at all times, the most important consideration of the Court.

What does this actually mean, though?

The legislation spells it out clearly. When determining what a child’s best interest are, the Court considers the things set out in section 60CC of the Family Law Act 1975. These include primary and secondary considerations.

Primary considerations

- Each child has the right to have a meaningful relationship with both parents.

- The need to protect the child from any harm (whether it be physical or psychological harm, from exposure to abuse, neglect or family violence).

The Court places greater weight on the need to protect the child from any harm or family violence over the child having a meaningful relationship with both parents.

Secondary considerations

- Any views expressed by the child and any factors at the Court thinks are relevant to the weight it should give to the children’s views (such as the child’s maturity levels or level of understanding).

- The nature of the relationship of the child with each of the parents and any other persons (including any grandparent, guardian, carer or other relative).

- The extent to which each of the parents takes, or fails to take, the opportunity:

- to participate in making decisions about major long-term issues in relation to the child (such as decisions about the child’s health, name, living arrangements, cultural or religious upbringing and schooling)

- to spend time with the child

- to communicate with the child when he or she is not in their care.

- The extent to which each of the parents has fulfilled, or failed to fulfil, the obligations to maintain the child.

- The likely effect of any change in the child’s circumstances, including the likely effect of any separation from:

- either of the parents, or

- any other child or person with whom the child has been living;

- The capacity of the following people to provide for the needs of the children (including emotional and intellectual needs):

- each of the parents, and

- any other person (including any grandparent, guardian, carer or other relative of the child).

- The maturity, sex, lifestyle and background of the child and either of the child’s parents and any other characteristic of the child that the Court considers relevant.

- The attitude to the child, and to the responsibilities of parenthood, demonstrated by the parents.

- Any family violence involving the child or a member of the family.

- Any other fact or circumstances that the Court thinks is relevant.

Parental responsibility

Parental responsibility in Australia means all the duties, powers, responsibilities and authority that a parent has in relation to their child. It’s a legal term, set out in section 61B of the Family Law Act 1975, and applies to all parents of a child under the age of 18 years – whether biological or adoptive.

This responsibility remains in place, and does not change, if parents separate, divorce, re-partner or remarry.

A person with parental responsibility is responsible for all major matters relating to the child, such as the care, welfare and development of the child. These matters are the long-term decisions rather than the short-term decisions – things like the child’s health, name, living arrangements, cultural or religious upbringing and schooling.

If you’re a parent of a child under the age of 18 years, you’re presumed to have parental responsibility.

What is equal shared parental responsibility?

Equal shared parental responsibility means both parents of a child under the age of 18 years old have a role in making decisions about major long-term issues that affect the child.

Equal shared parental responsibility does not necessarily mean equal time care arrangements.

In Australia, it is presumed that each parent has equal shared responsibility. This presumption encourages parents to co-parent cooperatively and consult with each other when making any major long-term decisions about a child. For example, if a child is sick and in need of medical treatment, the parent who has the child in their care must consult the other parent before making any decision about the treatment.

Until Orders are made by the Court or by consent, it is presumed that both parents have equal shared parental responsibility.

If the Court finds there is a presumption of equal shared parental responsibility between the parents – meaning there are no circumstances of family violence or child abuse – the Court must consider making an Order for the children to spend equal time with each parent.

An equal time arrangement is one that is:

- reasonably practicable, and

- in the best interests of the child.

However, if the Court does not find that an equal time arrangement is reasonably practicable, then it must consider making an Order for the child to spend substantial and significant time with each parent provided this is:

- reasonably practicable, and

- in the best interests of the child.

Does the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility always apply?

When the child is in the care of either parent, the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility does not apply to decisions about short-term matters and everyday activities. For example, decisions about what the child wears or eats, and what time they go to bed, do not have to be made jointly with the other parent.

The presumption also does not apply if there are reasonable grounds to believe one parent has abused, been violent against or used threatening behaviour towards the child, or any other child or family member in either parent’s family.

What happens if there is no equal shared parental responsibility?

You can apply to the Family Court for an Order for sole parental responsibility. This Order will only be made where the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility is not in the best interests of the child.

Parenting Orders may still include time that the child lives with or spends time with the other parent. However, the Court may also make an order for one parent (or non-parent carer, such as grandparents or other family members) to have only supervised time with the child if they are considered to be at risk of exposing the child to any family violence or child abuse.

If an Order for sole parental responsibility is sought, the Court may make one of the following orders:

- that one parent has sole responsibility for all, or part, of the major long-term decisions of the child without having to consult the other parent (or non-parent carer)

- that the child live with one parent only (which could also mean the child spends only supervised time with the other parent)

- specific terms about the time the other parent spends, or communicates, with the child.

Any parent, or non-parent carer, can make an application to the Court for a sole parental responsibility Order, or to vary existing Parentings Orders, if they are concerned for the welfare and care of the child/ren.

For a Court to make a decision about this matter, the person applying for the Order must provide evidence to satisfy the Court that the other parent is not fit to care for the child and that equal shared parental responsibility is not in the best interests of the child.

This evidence may include police or medical reports, psychology assessments, or other relevant witness statements. The Court may also consider evidence about the mental and physical health of either parent.

This is a very serious and complex area of family law. If you wish to make an application for sole parental responsibility, we strongly urge you to get legal advice. For legal advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

What is equal time?

An equal time arrangement in one where the child spends half of their time with each parent.

This is usually worked out on a fortnightly basis. An equal time Order might mean a “week about” arrangement, which is where the child spends one week with one parent and then the next week with the other parent. Care might also occur on a different fortnightly routine that suits the parents, provided the child is ultimately spending equal time with each parent.

What is “substantial and significant time”?

When a child lives primarily with one parent, they might still spend “substantial and significant time” with the other parent by spending time with both parents during the week, weekends, school holidays and on special occasions (such as birthdays, Father’s day and Mother’s day).

This arrangement allows both parents to be involved in the child’s daily life as well as sharing in special and other significant events.

What is “reasonably practicable”?

When the Court considers whether to make an Order for equal time, or substantial and significant time, it must consider whether it is “reasonably practicable” to do so. Working out what is “reasonably practicable” involves considering:

- how far apart you and the other parent live from each other

- how far apart you and the other parent live from the child’s school or daycare

- your capacity, and the other parent’s capacity, to implement the arrangements (for example, can you easily communicate with each other and resolve difficulties that might arise in implementing the parenting arrangement?)

- the practical impact that the arrangement would have on the child.

Rights in Parenting Matters

Rights of the child

The only rights recognised in parenting matters under the Family Law Act 1975 are the rights of the child.

The Family Court of Australia and the Federal Circuit Court of Australia have the discretionary power to make whatever Parenting Orders they consider appropriate when making a decision about what is in the best interests of the child.

Rights of parents after separation or divorce

There is a common misunderstanding of parents rights under the Family Law Act 1975 in relation to parenting matters.

A parent does have the right to make major long-term decisions about a child’s education, religion or culture, discipline, living arrangements, and health. However, a child’s rights will always come before parents’ rights in the Australian family law system.

Ultimately, the Court’s main focus is to ensure each child has a meaningful relationship with both parents and is not affected by family violence or child abuse.

The duties of a parent include:

- protecting their child from any harm, including family violence or child abuse

- providing their child with food, clothing and a home to live in

- supporting their child financially

- providing safety, supervision and control

- providing medical care when necessary

- providing an education.

The Court will consider the facts of each parenting matter and determine whether or not parents will have shared equal parental responsibility, and what living arrangements suit the best interests of the child.

Grandparents, step-parents, other family members and significant others

Any party who is interested in the welfare of a child can make an application to the Court for Parenting Orders. In most circumstances, this is the parents of the child – whether biological or adoptive. However, it can also be:

- the grandparents of the child

- an aunty or uncle, or any other family member of the child

- a step-parent of the child

- the guardian or carer of the child

- any other significant person who is concerned for the welfare of the child.

If you wish to make an application to commence proceedings in parenting matters, you’ll need to follow the same Court processes whether you are a parent or another person.

Independent Children’s Lawyer

An Independent Children’s Lawyer (ICL) represents the child’s best interests. They make sure that the child is the focus of any decisions made about parenting arrangements, such as parental responsibility and the time a child lives with or spends with each parent.

The role of the ICL is to:

- consider the views of the child

- organise necessary evidence to be put before the Court, such as expert evidence from a social worker or medical professional

- facilitate the participation of the child in the Court proceedings (taking into account the child’s age and maturity and the circumstances of the case)

- act as an honest and neutral negotiator between the child and the parents during the Court proceedings and in negotiations, if appropriate.

Methods of resolving your parenting matter

Negotiation

Negotiations about parenting matters can happen between you and your former spouse or de facto partner directly. If you have legal representation, your lawyers can handle negotiations.

Negotiations can happen in writing, verbally or, where appropriate, in person.

If you are having trouble reaching an agreement in relation to parenting matters, we recommend you get independent legal advice to assist in your negotiations. It is better for everyone – especially the children – to reach an agreement rather than commence Court proceedings.

For help in negotiating parenting matters, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Family Dispute Resolution

Family Dispute Resolution (FDR) is another term for mediation. It involves discussions between the parties and a jointly appointed FDR Practitioner – with or without legal representatives present.

An FDR Practitioner is usually a senior member of the legal profession, who may be a social worker, ex-Family Law Judge, barrister or solicitor. The role of the FDR Practitioner is to assist you and your former spouse or de facto partner to reach common ground about parenting matters and reach an agreement which can be formalised.

It is common for an FDR to take an entire day. The cost of an FDR depends on the complexity of the parenting issues in dispute. Both parties are generally expected to share the costs equally.

If no agreement can be reached at FDR, the FDR Practitioner will issue a Section 60I Certificate.

The Section 60I Certificate allows you to commence proceedings in Court. It confirms you and your former spouse or de facto partner did attend, or attempted to attend, the FDR to resolve your parenting matter. An FDR Practitioner will also issue this certificate if either party was formally invited to attend the FDR but refused or failed to attend.

You can only commence Court proceedings for parenting matters if you have a Section 60I Certificate, unless yours is an urgent parenting matter (such as where there is serious family violence involved or a parent has removed the child from their home, state or country).

The collaboration process

The collaborative process is commonly referred to as the “respectful divorce process”. It is a very different form of dispute resolution process.

Collaboration requires you and your former spouse or de facto partner to make a commitment to not commence (or threaten to commence) Court proceedings for your parenting matters. Instead, you both have face-to-face meetings, with your family lawyers, to reach an agreement. The “round table” discussions also include, where appropriate, accountants, financial planners and counsellors. This allows you both to reach an agreement that is mutually acceptable without attending Court.

This approach ensures that any children of a marriage or de facto relationship are not caught up in the potentially damaging effects of litigation. The process allows parties to engage openly and fully with each other (including meeting disclosure obligations).

However, both parties need to be prepared to take responsibility for moving forward through the separation and finding common ground in relation to a solution for all of the issues in dispute.

Once an agreement has been reached, our family lawyers will assist you in formalising the agreement and lodging it with the Court.

Court Ordered Child Dispute Conference

A Child Dispute Conference (CDC) is a meeting ordered by the Court with a family consultant.

The CDC is a meeting with the family consultant and the parents (or non-parent carer) without any legal representatives and without any child present. As it is Court ordered, you must attend. If you don’t, the family consultant will inform the Court.

A family consultant is usually a qualified social worker or psychologist who has experience and skills in working alongside families. They are appointed by the Courts and provide expert evidence on behalf of the Court. They assist both the Court and the parents to achieve the best outcome for the child.

The purpose of a CDC is to give the Court a preliminary understanding of family dynamics and identify the parenting issues in dispute. Like the Court, this conference focuses on what is in the best interests of the child. It is also a mechanism to help parties come to an agreement about parenting matters.

It is important to know that the CDC is confidential and private, but the evidence will be given to the Court to assist in making interim or final Parenting Orders.

There are no fees associated with a CDC as it is ordered by the Court and forms part of the Court’s evidence.

We have reached an agreement about parenting matters: How to formalise parenting matters

After separation or divorce, it is important that your child or children are cared for and supported.

If the parents reach an agreement, that agreement can be formalised by:

- Parenting Plan, or

- Consent Orders.

It is important to get legal advice before signing any documents in relation to parenting matters.

For legal advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Parenting plans

If an agreement can be reached, you may enter into a Parenting Plan. This document is any written, signed and dated agreement made between parents. This can be made before either party obtains legal representation.

A Parenting Plan is only valid if it has been entered into without duress or any threats of coercion from the other parent.

Some of the issues that a Parenting Plan may cover are:

- who has parental responsibility

- who the child will live with and who they will spend time with

- details of what communication the child will have with both parents when in the other parent’s care

- consultation between the parents who share parental responsibility

- what processes are in place to resolve any future disputes about the child

- what processes are in place to change the plan in the future if circumstances change

- any other aspect of the care, welfare and development of the child.

A Parenting Plan is not legally binding or enforceable, but it does allow you and the other parent to be flexible if circumstances change.

The Court will consider the terms of the Parenting Plan if proceedings are commenced, but they will ultimately make a decision based on the best interests of the child.

The risk of entering into a Parenting Plan is that you will not be able to bring contravention proceedings if one party does not comply with the terms of the agreement.

If you and your former spouse or de facto partner have final Parenting Orders, they will override any future Parenting Plan entered into if the terms of the orders provide so. Otherwise, if there is no Order stating that, and there are changes to your circumstances and both parents agree to amend the Parenting Plan, the Parenting Plan will override any previously-made Orders (provided it was entered into without any duress, threat or coercion).

Unless you and your former spouse or de facto partner are amicable and have a strong basis of trust, then we recommend you enter into Consent Orders over a Parenting Plan.

Like any family or relationship law matter, we recommend you get legal advice before you sign any agreement or document that contains arrangements for the care and support of your child.

Keep in mind that any document could be considered by the Court to be a Parenting Plan, even if you did not consider it to be such a plan when you signed the agreement.

For legal advice on parenting plans or other family law matters, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Consent Orders

If you and your former spouse or de facto partner want to make your agreement about parenting matters legally binding, we recommend you enter into Consent Orders.

To get Consent Orders, you and your former spouse or de facto partner do not need to attend Court.

You will, however, need to file the following documents with the Family Court of Australia:

- Minute of Orders, signed by both parties to the agreement

- Application for Consent Orders.

You’ll also need to pay a filing fee. If you have a concession card this may reduce the filing fee payable.

Once filed, the Registrar of the Family Court of Australia will review the terms of the Orders. If they are considered appropriate and in the best interests of the child, the Court will seal them and the Orders will become final. Once final, the Orders are legally binding and enforceable.

Once final Parenting Orders have been made, the only way to amend or vary the Orders (besides if the agreement was entered into by fraud, duress, or misrepresentation) is if the Court is convinced there has been a significant change in circumstances that warrant revisiting the Orders previously made.

The benefit of entering into Consent Orders is their enforceability – a contravention application can be made if either of you do not comply with the Orders.

The risk of entering into Consent Orders is that if any amendments are required in the future, you’ll need to satisfy the Court that there has been a significant change in circumstances that require the Orders to be changed. This can be difficult and costly.

We CAN’T reach an agreement about parenting matters: What happens next?

If an agreement can’t be reached by way of negotiations , you will need the Court to make an Order on your behalf. The Court will divide your property interests in what is called a just and equitable (otherwise, fair and reasonable) manner based on the circumstances of your marriage or de facto relationship and the parties future needs.

Before making an application to commence proceedings, you will need to:

- inform your former spouse or de facto partner, or their legal representation, that you intend to make a claim in Court, and

- have attempted to settle the matter and satisfy your disclosure obligations (in some cases the other party will not produce their disclosure documents, in which case you can make an application to the Court for orders).

You can prepare an application for property settlement and spousal maintenance family law matters or our family lawyers can help you with this.

If you choose to represent yourself in Court proceedings, we highly recommend you seek legal advice before you do so. You should completely understand your rights, responsibilities and obligations prior to filing your application and throughout the entire process.

For family law advice tailored to your family law dispute and circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Making a Court application for property proceedings

When you make an application to the Court to commence proceedings for property settlement matters, including spousal maintenance, you must file the following documents with the Court:

Initiating Application

This sets out the details of the relationship, and the final Orders you are seeking in relation to the division of the net asset pool and spouse maintenance payments. You can also seek interim Orders, such as attending family law mediation, obtaining joint valuations, payment of spouse maintenance for a period of time, selling a property, or any other order concerning something that will occur before final orders are made.

Financial Statement

This details the Applicant’s financial position (income, expenses, assets, liabilities and superannuation entitlements), the known asset pool, if possible, and shows why a party needs to claim spousal maintenance.

Affidavit

This sets out your written evidence, including reasons why the Court should make the Orders you are seeking.

You’ll also need to pay a filing fee. If you have a concession card this may reduce the filing fee payable.

You will need to serve the documents on the other party once you have commenced proceedings. You can serve the documents by hand, post, email, facsimile or upon the solicitors acting for the other party (if they have agreed to accept service).

You can commence proceedings with or without a solicitor. However, given the complexity of family law matters, we recommend you obtain family law advice before commencing family law proceedings.

You should understand how the Court process works and get family law advice about what range of outcomes you would expect in your circumstances if your matter was to be decided by the Court.

You can also find tips on how to write an affidavit or call our family lawyers on 02 9262 4003 to obtain advice tailored to your family law dispute and circumstances.

Response to Application for Property Settlement Proceedings

If you have been served with an Initiating Application for Property Orders, you will need to file the following Court documents in response, setting out your position:

Response to Initiating Application

This is a response to the issues in dispute raised in the Initiating Application and provides alternative evidence, if necessary, to support your case.

Financial Statement

Details of the party’s financial position (income, expenses, assets, liabilities and superannuation entitlements), the known asset pool, if possible, and, if relevant, why the party needs to claim spousal maintenance.

Affidavit

This should set out your written evidence, including reasons why the Court should make the Orders you are seeking.

You’ll also need to pay a filing fee. If you have a concession card this may reduce the filing fee payable.

The documents will need to be served on the other party in the proceedings.

Given the complexity of family law matters, we recommend you obtain family law advice before responding to an Initiating Application. You should understand how the Family Court related process works and get family law advice about what range of outcomes you would expect in your circumstances if your matter was to be decided by a Court.

For family law advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

The Court process

What happens when parenting proceedings commence?

Non-urgent parenting settlement matters

Non-urgent parenting settlement matters are those where there is no risk of family violence or abuse.

Every family law or relationship law matter is different and the outcome will vary depending on the specific circumstances of your marriage or de facto relationship. Most importantly, outcomes will vary depending on any children of your marriage or de facto relationship.

When commencing proceedings, there is a six-step process.

Step 1: Pre-action procedures (Family Dispute Resolution)

Before you file an application in the Court for parenting matters, you must:

- read the Court’s “Marriages, Families and Separation” brochure, and

- make a genuine effort to resolve your parenting matters through Family Dispute Resolution (FDR).

This applies to all parenting matters unless there is risk of being exposed to family violence or your matter falls within one of the exceptions (such as, one parent breaching a family law Order).

You can choose to attend FDR through a government funded program (such as Relationships Australia) or through a private FDR with a specialised FDR practitioner (usually a senior member of the legal profession, such as a social worker, ex-Judge, barrister or lawyer).

If you can’t reach an agreement, the FDR Practitioner will issue a Section 60I Certificate. This allows you to commence proceedings for parenting matters in Court and confirms you and your former spouse or de facto partner did attend, or attempted to attend, the FDR to resolve your parenting matter. A certificate will also be issued if both parties were formally invited to attend the FDR but one party refused, or failed, to attend.

If an agreement can be reached at FDR, you and your former spouse or de facto partner will sign up to a Parenting Plan on the day. Depending on your circumstances, you can file Consent Orders with the Court to make the agreement about parenting matters legally binding and enforceable.

Read more about Consent Orders or call us on 02 9262 4003 to find out more about formalising your agreement.

Step 2: Application to Court to commence proceedings

To commence parenting proceedings, you need to file the relevant documents in either the Federal Circuit Court of Australia or the Family Court of Australia. You can read more about making an Application for Parenting Proceedings in Court.

The other party will need to provide a Response to Initiating Application before the first Court date. If they don’t, the Court may make Orders on their behalf in their absence – either on an interim or final basis.

Step 3: First Court hearing date

When you commence parenting proceedings, you receive a date for your first Court hearing. You (or your legal representative on your behalf) will need to appear before a Judge or Registrar.

If the other party doesn’t attend, and the Court has significant evidence, final Orders may be made. However, in most circumstances, interim Orders will be made and must be served on the other party.

Interim Orders assist in progressing your matter. They can Order both parties to attend mediation (also known as a child dispute conference), attend a parenting program to assist with co-parenting, or request further evidence (such as a Family Report) to be provided to the Court – which will occur before final Orders are made.

You can seek interim or final Orders in your Initiating Application, or Response, which can be amended at a later date.

It is important to know that the Court will disregard the terms sought in an interim Order when making final Parenting Orders, in accordance with their obligations under the Family Law Act 1975.

Step 4: Attendance at Court Ordered Child Dispute Conference (or other dispute resolution)

At the first hearing date, the Judge will make specific interim Orders around whether you and your former spouse or de facto partner attend a child dispute conference.

In some circumstances, the Judge may order you and the other parent to attend a private FDR or mediation or a legal aid conference (if there is an ICL appointed and the parties cannot afford to attend one of the other dispute resolution forums).

The purpose of this interim event is to determine what issues remain in dispute and how to best resolve them. This event must occur before the next Court hearing.

If an agreement can be reached, your family lawyers will file the draft Orders setting out the agreement to the Court for approval. If the Court considers the parenting agreement to be in the best interests of the child or children, then it will make the Orders and they will be binding on both parties. If you are self-represented you will need to attend the next Court hearing to hand the Consent Orders up to the Judge for review and approval.

If an agreement can’t be reached, the family consultant will provide a Family Assessment Report to provide the Court with evidence on how to proceed with your matter. This is the Court’s evidence and will assist the Court in making final Parenting Orders.

Given the complexity of family law matters, we recommend you obtain legal advice before signing any agreement or commencing proceedings. For legal advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Step 5: Obtaining a Family Assessment Report

If you can’t reach an agreement at the Child Dispute Conference or private mediation:

- the family consultant will issue a Family Assessment Report (if you attended a Child Dispute Conference), or

- you will need to attend an interim hearing for the Court to make a further interim Order that a Family Assessment Report be obtained (for those who attended a private mediation or a Legal Aid Conference).

The family consultant will interview both parents and any other person the Court believes should be interviewed, such as adult siblings, step or half siblings, or grandparents.

In some circumstances, the child will be interviewed – usually separately from the parents. The family consultant may ask for the parents to interact with the child in some circumstances.

The Family Report is written by a family consultant, who is appointed by the Court. The report provides the Court with evidence about the arrangements for the child.

When the family consultant prepares the report, they identify all of the issues in dispute and provide recommendations to the Court about the child’s future care, welfare and developmental needs. Above all, the child’s best interests are the focal point of any report.

The Family Report is issued to the Court and the legal representatives of the parties, or directly to both parents, before the next Court hearing.

Depending on the issues of the case, you may need more than one interim hearing. Ultimately, though, if you can’t reach an agreement your matter will be set down for a trial date before a Judge.

If you receive the family report and you don’t agree with the evidence contained in it, you may have an opportunity to challenge the contents of the report at the trial through cross examination. However, you’ll need to inform the family consultant in writing, at least 14 days before the trial date, that you intend to cross-examine them at the trial.

It is important that you do not show the family report to any other person, including other family members or friends, unless the Court has given permission to do so. If you do so without permission, you are committing an offence under section 121 of the Family Law Act 1975.

Step 6: Trial – Final Parenting Orders made

The Court then considers all of the evidence to make final Parenting Orders that are in the best interests of the child. The Orders will remain in place until the child turns 18 years old.

The Court is very reluctant to vary final Parenting Orders. However, final Parenting Orders can be changed if you can satisfy the Court that there have been “significant changes” in circumstances since final Parenting Orders were made. This is known as the Rice v Asplund rule and is there to protect children from being exposed to ongoing family law disputes.

Some examples of significant change are:

- a parent wanting to relocate a child to another city, state or country

- a significant period of time passing between final Parenting Orders and the Initiating Application for parenting matters

- a child suffering or being subject to family violence or child abuse

- one of the parents or a child becoming terminally ill or disabled

- not all evidence being provided when final Orders were made

- the parents agreeing to vary the Orders and entering into a new parenting plan (or requesting that Consent Orders be made to vary the existing final Parenting Orders).

This is a complex area of family law. If you wish to enter into negotiations with the other parent or commence proceedings to vary the final Parenting Orders, we highly recommend you get legal advice.

For legal advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Urgent parenting matters

If you need to commence urgent parenting proceedings, you need to follow steps 2 through to 6, as detailed above. You do not need to provide a Section 60I Certificate.

You will, however, need to give details and examples in your affidavit about the history of the family or domestic violence that you or the children have suffered, or are continuing to suffer from, or detail why your matter is urgent.

An urgent application may be made for parenting matters if there is family violence in the marriage or de facto relationship.

An urgent application may also be made if one of the following exemptions applies:

- the Court is satisfied there are reasonable grounds to believe that there has been, or there’s a risk of, child abuse or family violence by a parent if there were to be a delay in commencing Court proceedings

- where one parent is unable to participate in FDR effectively (for example, due to an incapacity to participate in FDR or geographical remoteness)

- if someone contravenes existing final Parenting Orders that were made by the Court in the first 12 months and that person shows a serious disregard to their obligations under the existing Orders

- any other reason the Court considers reasonable that a Section 60I certificate was not required in the circumstances.

Advice about urgent parenting matters will vary depending on the complexity of your matter and whether you will be filing an application in the Family Court of Australia or the Federal Circuit Court of Australia.

For legal advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Other considerations in property settlement matters

Family violence and negative contributions

In property settlement and spousal maintenance matters, the Court considers how much each party contributed, whether directly or indirectly, to the financial relationship. This can be done through financial contributions, non-financial contributions and parent and homemaker contributions.

The conduct of each party is usually not considered by a Court, unless there was serious family violence in a marriage or a de facto relationship. This can result in a “negative contribution”, though it can be a difficult thing to prove.

What is family violence?

The Family Law Act 1975 defines family violence as any behaviour that is violent or threatening, or any other behaviour that coerces or controls another member of the person’s family or causes that family member to be fearful.

The following are examples of family violence:

- assault (including physical, emotional, financial, sexual assault or other sexually abusive behaviour)

- stalking

- making repeated derogatory taunts

- intentionally damaging or destroying property

- intentionally injuring or causing death to an animal

- financial or social control or coercion, including:

- unreasonably denying financial independence (for example, by controlling what a family member spends or how they access their money)

- unreasonably withholding financial support for reasonable living expenses to a dependent

- preventing someone from making, or keeping connections, with their family, friends, culture or religion

- unlawfully depriving someone of his or her liberty.

The Court may consider other circumstances or behaviours that fall within the definition of family violence.

Does serious family violence affect the outcome of property settlement matters?

Even though the Family Law Act 1975 does not explicitly state that serious family violence can result in a negative contribution, the Court has the discretionary power to make any order it considers appropriate when making an adjustment of interests and deciding a fair property settlement.

Case law shows that judges are willing to determine that serious family violence can result in a negative contribution.

In 1997, the Family Court of Australia considered whether family violence could alter the outcome of a property settlement in the case of Kennon v Kennon.

In this case, the husband had a significantly higher income, but the wife had brought significantly more assets into the relationship. The wife alleged that the husband had caused serious family violence, which involved several specific encounters of physical violence. She argued that his conduct should result in an adjustment, in percentage terms, in her favour.

In making its decision, the Court considered whether:

- circumstances of “violent conduct” was established

- the violent conduct had a visible impact on the wife

- the wife’s contributions to the relationship had become significantly more difficult because of the domestic violence.

Ultimately, the Court found that a successful negative contribution argument, based on serious family violence affecting the victim’s contributions to the relationship to become more difficult, requires specific evidence to substantiate the argument. The Court made it clear that a successful negative contributions argument would only apply in rare circumstances.

In the later case of Baranski & Baranksi & Anor, the Court followed the Kennon decision but made it clear that family violence could be considered to make contributions more difficult regardless if the family violence happened during the marriage or de facto relationship or after the date of separation or divorce.

If you have suffered from significant family violence during your marriage or de facto relationship, and wish to run a negative contributions argument in Court, you will need to ensure that the Court is satisfied there is a causative link between the family violence and the loss that was suffered. You will need to provide sufficient evidence to support this argument, such as expert evidence from a psychiatrist or psychologist. If evidence can prove that loss has been suffered, then a Court will make an adjustment, in percentage terms, in favour of the person who suffered from the family violence.

Ultimately, it is the Court’s discretion as to whether the serious family violence is so significant it can be seen as a negative contribution. That means, the Court will make decisions on a case by case basis.

This argument is very difficult and complex to make before a Court due to the strict evidence required to meet the threshold.

If you have experienced, or continue to experience, serious family violence, then we highly recommend you get family law advice and contact Police. Contact our experienced family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003 to arrange a free, no-obligation initial consultation.

Children: effect on property settlement matters

Will there be an adjustment if there are children in the marriage or de facto relationship?

When the Court is considering whether any adjustments, in percentage terms, can be made in relation to the future needs factors (section 75(2) Family Law Act 1975), it will take into account whether either party has:

- the care or control of a child of the marriage or de facto relationship

- any commitments and responsibilities to care and support any other person, including a child, from another marriage or de facto relationship (for example, child support or maintenance).

The Court has the discretionary power to make an adjustment to reflect the dynamic of the parties’ future needs to ensure that everyone is taken care of.

Other Orders which may be sought in parenting matters

When making an application for Court Orders about parenting matters, it is important that you obtain legal advice as family law can be complex.

We are here to support you and help you navigate through these difficult times. Please call the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 400.

When making an application, you should also ensure you apply for all the Orders you are seeking on a final basis since it’s difficult to change or terminate final Parenting Orders.

Applying for a child passport or overseas travel

If either you or the other parent want to take your child overseas you will have to get consent, in writing, from the other parent – regardless of whether or not the child holds a current passport.

If you have written consent to apply for a child passport or overseas travel

If you have written consent from the other parent but the child doesn’t have a current passport, you need to apply for a passport. Both parents need to compete and sign a passport application on behalf of the child to make an application.

Once the passport is issued by the Australian Government, you will need to get written consent from the other parent every time you wish to take the child overseas. You do not have the automatic right to take the child overseas just because the child has a current passport.

You may want to put your agreement about international travel into either a Parenting Plan or Consent Orders to ensure there are no future issues with obtaining written consent from the other parent.

If you DO NOT have written consent to apply for a child passport or overseas travel

If the other parent doesn’t agree to you applying for a child passport, then you have the following options:

- writing to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade requesting they consider issuing a child passport due to special circumstances

- making an application to commence proceedings in relation to parenting matters, where a Judge can determine whether an Order for international travel is allowed (in these circumstances the Court will usually grant specific Orders for obtaining a child passport and include terms for overseas travel.

Concerned that the other parent may take your child overseas without permission?

If you have concerns that the other parent may take your child overseas without your permission, you can:

- Lodge a Child Alert Request

If the child does not have a child passport, then you can lodge a Child Alert Request at any Australian Passport Office to prevent a child passport being issued.

This alert lasts for 12 months and you will be notified if an application is made.

This will not prevent a person taking the child overseas if they hold a current passport.

- Make an application to the Court

You can apply to the Court, seeking an Order that:

- prevents a child passport being issued

- seeks a Child Alert Order, which can stay in place until the child turns 18 years old (this does not stop a child leaving Australia if they have a current Australian or international passport)

- requires a person to deliver the child’s passport, and the accompanying parent’s passport, to the Court

- the child’s name be added to the Australian Federal Police’s Watch List (which prevents the other party and your child from leaving the country until a further Order is made and requires a Court Order if you wish to travel overseas with your child).

Australia has an agreement with other countries to return a child if they have been taken without permission from Australia. This agreement is the Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (The Hague Convention) which provides a list of the countries that are a part of the agreement.

If your child has been taken overseas without your permission, we strongly recommend you obtain urgent legal advice. Contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003 for immediate

Relocation Orders

After separation or divorce, there may come a time when you want to relocate to another city or town, whether that is in the same state or territory that you currently reside in, interstate or overseas. This is known as relocation.

You may be wanting to move for a job opportunity or to be closer to family or support. No matter what the reason is, you will need to get written permission from the other parent before you move or make the decision to move, as it may significantly reduce the time that they can spend with their child.

If you do wish to move, and you don’t have permission from the other parent, you will need to apply for a Relocation Order. When making this application, you must provide good reasons for why the proposed relocation is in the best interests of the child. Alternatively, the other parent can make an application to the Court for an Order to be made to stop the relocation of the child happening.

What factors does a Court consider when determining whether a Relocation Order should be made

When an application for a Relocation Order is made to the Court, the Judge will consider the following factors:

- whether it is in the child’s best interests in having a meaningful relationship with both parents

- protecting the child from any harm or abuse, including psychological, physiological, or family violence

- the views of the child (depending on their age and maturity)

- the nature of the child’s relationship with both parents and significant others such as grandparents and other family members

- whether both parents are able and willing (including financially) to facilitate and encourage a meaningful relationship between the child and the other parent

- how the changes are likely to affect the child’s circumstances

- the maturity, sex, lifestyle and background of the parents and the child

- any other consideration the Court believes is relevant.

Recovery Orders

The Family Law Act 1975 governs the location and recovery of a child that is taken from a parent, guardian or carer without their permission.

Applications for Recovery Orders are usually given top priority in Court proceedings about parenting matters.

A Recovery Order is made by the Court when a child has been taken by the other parent, or another person. A Court has the discretionary power to make an Order requesting that the child be returned to either a parent of the child, a person who the child lives with or spends time with, or a person who has parental responsibility for the child. Again, the Court’s paramount consideration when making an Order is the best interests of the child.

Who can make an application for a Recovery Order

You can make an application for a Recovery Order if:

- there is a final Parenting Order in place which states that the child lives with, or spends time with, or communicates with you, or you are the parent, guardian, carer or any other person, who has parental responsibility of the child

- there is no Parenting Order in place but you are the parent, grandparent, or another person who is concerned about the child’s care, welfare and development.

How to make an application for a Recovery Order

To make an application for a Recovery Order you need to commence proceedings in the Federal Circuit Court (unless you have current Parenting Orders).

If you have not previously commenced proceedings, or don’t have Parenting Orders, then you can apply for Parenting Orders when you commence proceedings for a Recovery Order. You will need to be specific with the Orders that you are seeking, and we recommend you seek legal advice in these circumstances. For legal advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

You will also need to file an affidavit in support of your application. You should include the following information in your affidavit so that the Court can make an informed decision about the Recovery Order:

- short history of your relationship with the other parent who the child is currently with

- summary of any previous Court hearings or existing Parenting Orders

- details of where the child lives and who the child usually lives with and spends time with

- detailed summary of what you know about when and how the child was taken from you and not returned to you and any details of where the child may be (and why you believe they are there)

- details of any steps taken to locate or find the child

- why it is in the best interests of the child to be returned to you (giving evidence as to why or how it may impact the child if they are not returned)

- anything else relevant to your matter (including evidence in relation to a complaint or any issues that the other parent who has the child may have about you).

What Recovery Orders can a Court make?

A Recovery Order can include the following terms:

- authorising a certain person (such as a police officer or Australian Federal Police officer) to take steps to find, recover and return the child to their parent, guardian or carer (with a copy of the Order given to the authorised person so that they can action the Order)

- determining how the child is cared for until they are returned

- preventing the person from taking the child, without permission, in the future (which may be by authorising police to arrest that person, without a warrant)

- how, when and where the child is to be returned.

In certain circumstances, the Court will also make Orders it believes reasonable, such as a:

- Location Order (which requires a person to give evidence to the Court about the child’s location, or any other information that may assist in locating the child)

- Commonwealth Information Order (which requires a Commonwealth Government Department to give evidence to the Court about the whereabouts of the child’s location, or any other information that may assist in locating the child, such as Centrelink records)

- Publication Order (which gives the media permission to publish certain details, information and photographs of the missing child and of the person who has taken the child).

Once the child has been returned, you have a duty to notify the Court registry staff as soon as possible.

Parental alienation or alignment

Parental alienation happens when a parent, or another person, coaches or convinces a child to align with them and not the other parent. This can be done by brainwashing the child or giving the child information to convince them into thinking bad things about the other parent.

This is a very complex legal issue and you will need sufficient evidence to make your case. Alienation can be damaging to both the wellbeing and welfare of the child and your relationship with them.

If you are in this situation and your child has been, or is being, alienated from you then you should seek immediate legal advice. Contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003 to make a free, no-obligation initial consultation.

Contravention of Parenting Orders

Contravention of final Parenting Orders is a serious matter if the parent does not have a reasonable excuse and it can’t be resolved through Family Dispute Resolution.

What is a contravention?

A contravention of Parenting Orders means that one parent has disobeyed the terms of the Parenting Order.

It can happen where a parent simply makes no effort to comply with the Parenting Orders and does not have a reasonable excuse for contravening the Parenting Order. In other cases, the parent may deliberately prevent, or attempt to prevent, another person (who is a party to the Parenting Orders) to comply with the Parenting Orders.

A contravention could also happen where one parent refuses to deliver or return the child to the other parent or to a person that the child is meant to spend time with.

What is a reasonable excuse?

A person has a reasonable excuse for breaching a Parenting Order where:

- they believed they had to breach the Orders to protect a person or child’s health or safety

- the breach only continued for a period of time that was necessary to protect a person or child’s health or safety

- they did not understand they were breaching their obligations under the Orders.

What happens if a Parenting Order has been breached or contravened?

You can file a Contravention Application if you believe the other parent has breached, or is breaching, a Parenting Order and they do not have a reasonable excuse for the breach.

You and the other parent must make a genuine attempt to resolve the situation through Family Dispute Resolution. If no agreement can be reached, or the other parent refuses to attend or negotiate, then a Section 60I Certificate will be issued by the FDR Practitioner.

You can also file a Contravention Application directly with the Court by attaching an Affidavit that explains why you should be exempt from providing a Section 60I Certificate.

Making a Contravention Application should be a last resort – it’s always preferable for parents to resolve these issues.

How to file a Contravention Application

To commence proceedings when Parenting Orders have been contravened or breached, you need to file the following documents:

- Application – Contravention (setting out the details of the parties, the child, and current arrangements for the child)

- Affidavit (setting out details of the contravention of the Parenting Orders by the other parent, providing detailed and specific evidence)

- Section 60I Certificate from the FDR Practitioner or an Affidavit – non-filing of Family Dispute Resolution Certificate for urgent and serious matters

- copy of existing Parenting Orders.

No filing fee is required.

You need to serve the documents on the other parent, and any other parties, once the documents have been filed with the Court.

How the Court considers a Contravention Application

When the Court considers a Contravention Application, it will review the circumstances of the breach, including whether the breach occurred only once, or if was repeated, the severity of the breach and why the Order was breached.

What Orders can a Court make in response to a Contravention Application?

Before you file a Contravention Application, it is important to consider what outcome you want.

The Court has the power to make the following Orders:

- enforcement of the Order (so the arrangements under the existing Order continue)

- an Order to compensate a parent, or other party to the earlier Orders, for lost contact time, which may include the child spending additional time to make up for lost contact time

- any Order to vary or change the existing Parenting Orders

- an Order for a party, or both parties, to attend a parenting program

- a Costs Order, for one parent to pay some or all of the legal costs of the other party

- an Order that a party pay some or all costs incurred by the other party as a result of the breach

- an Order to “put a party on notice” (which means that if the contravening parent does not continue to comply with the current Parenting Orders then they will be punished)

- an Order punishing the contravening parent by way of a fine or imprisonment.

This can be a complex area of law to navigate. Before making a Contravention Application, we highly recommend you seek legal advice.

For legal advice tailored to your circumstances, contact the family lawyers at Ivy Law Group on 02 9262 4003.

Legal fees and Cost Orders in parenting matters

Legal fees in parenting matters

Section 117(1) of the Family Law Act 1975 states that each party to proceedings must pay their own legal fees, unless certain exceptions apply.

The Court does, however, have a discretion to make an Order for Costs.

Costs Orders in parenting matters

Ultimately, it is up to the discretion of the Court to consider making a Costs Order. Each matter is considered based on the relevant factors of the matter.

A Court will look at the circumstances of each matter by considering:

- financial circumstances of both parties

- whether either party is receiving legal aid funding for their parenting matter, and – if so – the terms of that funding

- conduct of the parties, in particular any failure to comply with the Court’s rules or legislation (for example, the failure of either party to meet disclosure obligations, provide answers to specific questions served on them by the other party or admit the truth of certain facts or provide authentic documents to the Court)

- failure to comply with Orders of the Court (this is not the same as a contravention of Orders)

- if a party’s application or response has been wholly unsuccessful in Court proceedings

- if any reasonable offers to settle proceedings, in writing, have been made by either party (for example, if a party does not accept an offer of settlement and achieves a worse outcome at trial)

- any other matters that the Court considers relevant.

In parenting matters, the Court will consider the financial circumstances of each of the parties. If it would be detrimental, financially, to one parent to make a Costs Order based on the relevant circumstances of the matter, the Court will be reluctant to make such an order.

How can Ivy Law Group help you?

Our family lawyers have extensive experience dealing with parenting matters and other legal issues surrounding children and family law.

If you’d like help navigating this area of law, get in touch with our Sydney family lawyers below.

FAQs about parenting and children

Equal shared parental responsibility means both parents of a child under the age of 18 years old have a role in making decisions about major long-term issues that affect the child.

Until Orders are made by the Court or by consent, it is presumed that both parents have equal shared parental responsibility.

This means that, unless the Court is satisfied and makes a determination that a parent has engaged in abuse of a child or family violence and that an Order for sole parental responsibility should be made, each parent shares equally in the powers and responsibilities to make decisions for their child including about education and long-term medical needs. Parental responsibility does not mean that each parent has a “right” to spend equal time with a child, however, a primary consideration for a Court in determining what is in a child’s best interests is the benefit to a child to having a meaningful relationship with both parents.

Parents are encouraged to agree on and the Court will, subject to the child not being exposed to abuse, neglect or family violence, support an equal time arrangement where it is:

- reasonably practicable, and

- in the best interests of the child.

A parent of a child under the age of 18 years, who has the care of the child, can make an application for child support from the other parent. This can be so even if the child lives with each of the parents. The amount paid depends on various factors including the income of each of the parents.

It doesn’t matter whether you were married to the other parent or whether you’re negotiating a property settlement, claiming spousal maintenance or have divorce proceedings on foot. The child support process can be dealt with separately from these other issues, orders and proceedings. In order to claim child support, both parents should generally be living in Australia, although there are mechanisms for enforcement in overseas countries depending on which Country the other parent resides in.

There are many avenues to explore if you and your former partner cannot reach an agreement about parenting matters. As always, it’s best to consult an experienced family lawyer who can provide tailored advice on how to best resolve legal disputes and make sure that you come to an agreement that will allow as much as possible, a seamless transition for the child from one parent to another. That is, having a parenting agreement or Orders that are very specific and detailed to both yours and your child’s needs with a view to avoid disagreements down the track about, for example, changeover days and times.

If you cannot reach agreement, other avenues include:

- Negotiation: Negotiations about parenting matters can happen between you and your former spouse or de facto partner directly. If you have legal representation, your lawyers can handle negotiations. Negotiations can happen in writing, verbally and, where appropriate, in person.

- Family Dispute Resolution: Family Dispute Resolution (FDR) is another term for mediation. It involves discussions between the parties and a jointly appointed FDR Practitioner – with or without legal representatives present. An FDR Practitioner is usually a senior member of the legal profession, who may be a social worker, ex-Family Law Judge, barrister or solicitor.

- Collaborative Law: Collaboration requires you and your former spouse or de facto partner to make a commitment to not commence (or threaten to commence) Court proceedings for your parenting matters. Instead, you both have face-to-face meetings, with your family lawyers, to reach an agreement. The “round table” discussions also include, where appropriate, accountants, financial planners and counsellors. This allows you both to reach an agreement that is mutually acceptable without attending Court.

A parenting plan is a written, signed and dated agreement made between parents. It can cover issues such as:

- who has parental responsibility.

- who the child will live with and who they will spend time with.

- any agreements about each parent’s location and if they are to remain living in a particular area.

- details of what communication the child will have with both parents when in the other parent’s care.

- consultation between the parents who share parental responsibility.

- what processes are in place to resolve any future disputes about the child.

- what processes are in place to change the plan in the future if circumstances change.

- details about how and when the child can travel or if travel is to be prohibited in certain circumstances.

- any other aspect of the care, welfare and development of the child.

It’s important to note that a parenting plan is not a legally binding document, but it does allow you and the other parent to be flexible if circumstances change.

Like any family or relationship law matter, we recommend you get legal advice before you sign any agreement or document that contains arrangements for the care and support of your child.

Your parenting matter will be heard in the recently amalgamated Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (FCFCA). For more information on how cases will be handled in the new court, see our article: “what does the Family Court merger mean for families?”

When determining what is in the child’s best interests, the Court considers the primary and secondary considerations as set out in section 60CC of the Family Law Act 1975.

The primary considerations are:

- Each child has the right to have a meaningful relationship with both parents

- The need to protect the child from any harm (whether it be physical or psychological harm, from exposure to abuse, neglect or family violence)

Secondary considerations consider a range of factors such as the nature of the relationship the child has with each parent, the extent to which the parent takes the time to participate in making decisions about major long-term issues in relation to the child, the attitude to the child and to the responsibilities of parenthood. For an exhaustive list, please see our section on “Children and Family Law.”

Once you reach an agreement with your former partner about parenting matters, that agreement can be formalised by:

- Parenting Plan, or

- Consent Orders

It is important to get legal advice before signing any documents in relation to parenting matters.

To get Consent Orders, you and your former spouse or de facto partner do not need to attend Court. You will, however, need to prepare and file the following documents with the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia:

- Minute of Orders, signed by both parties to the agreement

- Application for Consent Orders

Once filed, the Registrar of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia will review the terms of the Orders. If they are considered appropriate and in the best interests of the child, the Court will seal them and the Orders will become final. Once final, the Orders are legally binding and enforceable.

No, if there are parenting proceedings that have commenced and you have not obtained an Order to do so, you should obtain urgent legal advice.

If proceedings have not been commenced in Court, you should inform the other parent of your intention to relocate and in the absence of consent, obtain legal advice from an experienced family lawyer about whether you need to apply for a Court Order. It is best to have any agreement formalised in Consent Orders prior to your move.

If you move and either the other parent has not consented or there is no Court Order allowing you to relocate:

- the other parent may apply for a recovery order to have the child returned until the parenting matter is finalised; and

- the Court may not grant an order if the relocation would mean that the child is limited in the time they can spend with other parent that can’t otherwise be rectified by additional time in school holidays.

More information on this topic can be found under the heading “Recovery Orders”.

If you are a parent concerned that your child may be taken overseas without your consent, you should seek urgent legal advice and can contact one of our family lawyers on 02 9262 4003. This is critical if the child may be taken to a country that is not party to the convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (The Hague Convention) as recovery options are not available in those countries.

More information on this topic can be found under the heading “Other Orders.”